Modern slavery isn’t an offshore problem, it’s threaded through the very tourism experiences Australians buy and sell. As the travel industry races to go greener, experts warn it’s time to confront the human cost hidden in supply chains too. Because sustainability demands more than eco-pledges; it requires protecting the people who power travel, writes University of Tasmania’s NADUNI MADHAVIKA.

Tourism’s hidden human cost: Why modern slavery risks are closer than we think

When we picture travel, we often imagine beaches, sunsets and adventure, not exploitation.

But behind every dream getaway lies a workforce that makes those experiences possible: cleaners, cooks, drivers and guides. And, as sustainability experts are warning, those same workers can be among the most vulnerable to modern slavery.

Modern slavery doesn’t always look like what we think it does. There are no chains or cages. Instead, it hides behind withheld wages, unsafe recruitment practices, inhumane working conditions or contracts written in languages workers can’t read, understand or comprehend. And it’s much closer to home than most travellers realise.

It happens in Australia

Modern slavery is not a distant problem confined to factories overseas. It can surface within the operations and supply chains of tourism businesses: in cleaning services, hotel kitchens, luxury cruise ships, and even voluntourism and orphanage tourism.

Investigations in recent years have uncovered cases of deceptive recruitment, wage theft, passport confiscations and visa exploitation in Australia.

In recent conversations with sustainability managers, supply chain professionals, modern slavery experts, regulators and NGO leaders, a clear message emerged: the tourism industry knows modern slavery exists, but just a few know what to do about it.

One sustainability expert described tourism as “the perfect storm – seasonal work, subcontracting, language barriers and little oversight.”

From hotels and restaurants to tour operators and cruise lines, the risks are woven through the system. Cleaning staff working long hours with no contracts; backpackers and students underpaid in cash; suppliers of food, uniforms or linen operating far down the supply chain – invisible to the brands whose names appear on the brochures.

Yet when asked, there are still those who believe it doesn’t happen here in Australia.

Good intentions, weak systems

Australia’s Modern Slavery Act (MSA) 2018 was intended to drive genuine corporate accountability. It requires large companies to report on how they identify and manage risks of exploitation in their operations and supply chains.

At the University of Tasmania, our research examines how Australian tourism companies are complying and responding to the Modern Slavery Act. While the legislation has undoubtedly raised awareness, many experts we interviewed highlighted a critical gap between awareness and action.

As one sustainability consultant observed, “There’s a lot of talking and reporting, but very little actual due diligence. The system rewards disclosure, not change.”

For smaller tourism operators, particularly those below the $100 million reporting threshold, limited resources make compliance seem like a luxury in an industry still recovering from COVID-19. For larger players, the barrier is often fear, fear of what they might uncover if they scrutinise their supply chains too closely.

The result? Despite glossy sustainability statements, too many companies remain focused on appearance rather than impact.

One sustainability consultant noted, “The statements that I see being produced by tourism companies in Australia are at the lower end of the maturity scale. The piece that seems to fall down, actually, is the articulation of what an organisation’s supply chain looks like. But without that framing of what their supply chain looks like, it’s really hard to then explain the risks that sit within that supply chain”.

Protecting people

Over the past decade, sustainability in tourism has become a buzzword. Travellers are encouraged to reuse towels, offset carbon and avoid single-use plastics.

Travellers are provided with environmentally conscious amenities, including wooden accessories such as combs, toothbrushes and ear buds, as well as herbal or sustainably sourced toiletries. These steps matter, but they only tell half the story.

Ethical tourism has been reduced to eco-tourism. But sustainability isn’t just about protecting reefs and rainforests – it’s also, and should always be, about protecting people.

During an interview, one modern slavery expert noted, “We spent four weeks in Bangkok. The hotel we stayed in had sustainability messages posted all over the premises – non-plastic toothbrushes, everything recycled and so on. But because we were there for an extended period, we got to know some of the staff, and I can tell you that they were working far more hours than what would be considered acceptable, and they were not being paid overtime. It’s an industry where this kind of abuse is very easy to hide, and I think it’s happening everywhere”.

Human rights are an essential pillar of sustainability. A hotel may run on renewable energy, but if its staff are underpaid, overworked or afraid to speak up, the business isn’t truly sustainable.

One Modern Slavery expert noted, “In Australia, most hotels don’t actually own their sheets and towels – they use a laundry service. The laundry service owns the linens, so hotels need to work in partnership with those providers. Even people who work in the industry often don’t realise that’s how that part of the supply chain operates. There’s a lot of unpicking that needs to be done”.

These insights underscore a simple truth: true sustainability isn’t just about going green, it’s about going fair. Protecting people must sit alongside protecting the planet, especially in an industry built on connection, hospitality and care.

Industry pros note signs of progress

These examples show that meaningful progress is achievable when the industry shifts from competition to collaboration in addressing modern slavery risks.

- Industry collaboration in Australia: Leading travel brands have joined the Australian Travel Industry Association’s (ATIA) Modern Slavery Collaboration, establishing a shared learning platform that supports collective action and continuous improvement across the sector.

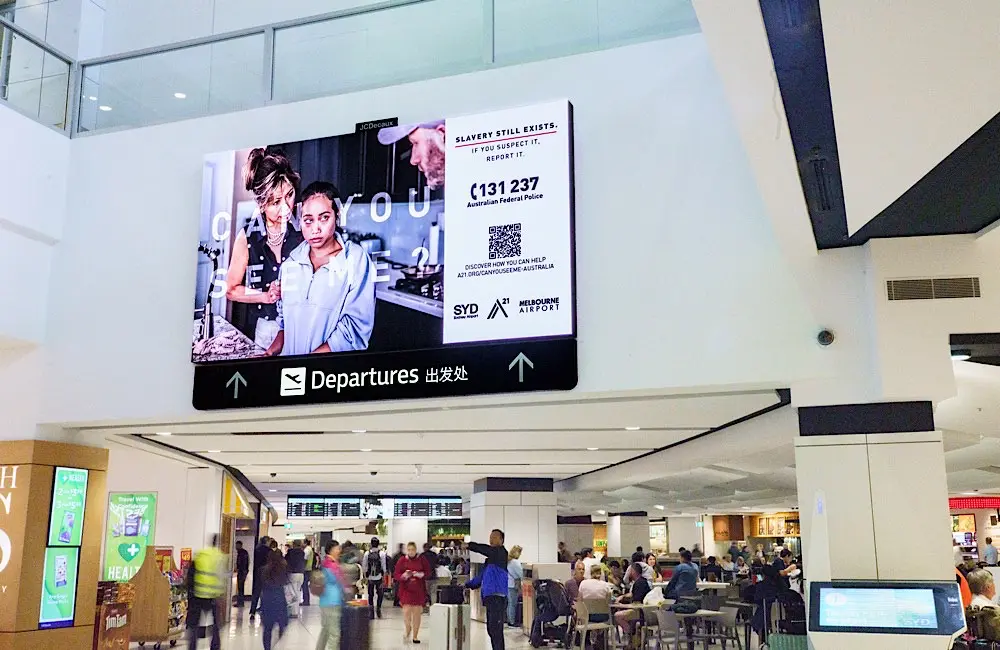

- Raising public awareness: The A21 “Can You See Me?” human trafficking campaign is bringing visibility to the issue through electronic signs and billboards featuring QR codes, the Australian Federal Police(AFP) hotline, and the message “If you suspect it, report it.”

- Global leadership: The World Travel & Tourism Council (WTTC) has created a dedicated Human Trafficking Taskforce, launched at its 2019 Global Summit in Seville. The Taskforce’s Action Framework focuses on four key areas – awareness-raising, education and training, advocacy, and victim support – to guide the sector’s collective response.

- Strengthening supplier capacity: Several Australian travel companies are investing in supplier training, translating key materials into local languages and partnering with ethical recruitment organisations to promote fair and transparent hiring practices.

- Also, the increasing visibility of official reporting channels, including the AFP’s confidential online reporting form for suspected human trafficking and modern slavery (https://forms.afp.gov.au/online_forms/human_trafficking_form).

Technology, transparency and trust

Experts say technology could play a bigger role, not to replace human judgment, but to support it.

AI-based supplier screening tools can help identify high-risk regions, while “worker-voice” apps like “Ask-your-team” allow staff to report exploitation anonymously.

But technology alone won’t solve the problem. What’s needed most is trust between companies, workers and the communities they operate in. It’s important to understand that empathy cannot be automated. You still need people trained to listen and respond.

What travellers can do

As travellers, we have more power than we think. We can:

- Choose operators that publish transparent modern slavery statements or partner with ethical travel bodies.

- Ask hotels and tour providers what they’re doing to protect workers.

- Support businesses that source responsibly and invest locally.

- Share stories that promote fair and inclusive tourism.

Every question asked, every ethical choice made, signals to the industry that travellers care, not just about destinations, but about the people who make those destinations possible.

Towards a truly sustainable future

Tourism, at its best, connects people, places, and cultures. Yet to truly live up to that promise, it must also ensure that no one is exploited along the way. Tourism and travel businesses sell joy and connection. But that promise means nothing if the people behind it are suffering.

For Australia’s tourism sector and the travellers who sustain it, the next frontier of sustainability isn’t just about going green, it’s about going fair.

By Naduni Madhavika, Dr Mansi Mansi, Associate Professor Rakesh Pandey and Dr Balkrushna Potdar – Tasmanian School of Business & Economics, University of Tasmania