Opened in 2013, Fogo Island Inn, located on the rugged shores of Newfoundland and Labrador in Canada’s east, is an extraordinary cultural and architectural masterpiece that blends luxury with community-driven values. Eighth-generation Fogo Islander Zita Cobb, founder of Fogo Island Inn, shared her story with Skift Editor-in-Chief Sarah Kopit at the recent Skift Global Forum. Karryon founder Matt Leedham reports from New York.

After a successful career in Silicon Valley’s tech industry, Zita Cobb returned to her roots a decade ago to help revitalise her community. Her vision was to build an iconic property that would act as a mediator between past traditions and future sustainability while offering an unparalleled guest experience.

The inn’s iconic design, which combines modernist architecture with traditional Newfoundland building techniques, has since garnered countless international recognition, including being awarded three Michelin Keys. But more than its aesthetic credentials, luxurious stays and North Atlantic vistas, Fogo Island Inn is a model for how hospitality can support and strengthen local communities.

Everything from the 29-room inn’s locally sourced cuisine to its handcrafted furnishings is deeply tied to the island’s heritage. Operating under the Shorefast Foundation, established in 2006 with two of Zita Cobb’s six siblings, Alan and Anthony, Fogo Island Inn transparently reinvests profits back into the community, making it a pioneering force in sustainable tourism and economic resilience.

I had the absolute privilege of witnessing Zita Cobb in conversation with Skift Editor-in-Chief Sarah Kopit on stage at the recent Skift Global Forum in New York. Cobb’s story and frank take on life and what tourism could and should look like were both refreshing and absolutely spellbinding.

Why did you decide to leave Silicon Valley and go back home to Fogo Island?

“Well, I’m an eighth-generation Fogo Islander, and no matter where you live on this planet, you probably know that smaller places are having a tough go of it. I looked at what was happening in my community and thought, “It’s my job to figure out how to put another leg on the economy.” How can we do it in a way that strengthens culture? This is, of course, what travel and hospitality can do. It doesn’t always, but it can. And I didn’t see a big lineup of people volunteering for that job, so I took the money from my career, and being a somewhat sane person, I went home and spent it.

“It always pissed me off to travel around the world and see amazing inns in remote places, and there are parts of the world that do it better in other places that are community-based. And I thought, what is wrong with us? We don’t have one of these because there’s nothing mediocre in any way in this place. So we’re going to build it in. We’re going to do it in a way that our job, my job, or all of our jobs in the present, is to mediate the relationship between the past and the future.

“If you ever want to talk about hospitality, we’ve got to think about humans. But if you think about humans, I haven’t met one, and that isn’t a physical creature. We’re embodied creatures, which means every night, you have to put your head down somewhere. We are social creatures, and we are meaning-seeking creatures. All of those things exist in place. And then we went through this weird kind of a time of thinking that we lived in a global village. Remember that nobody lives in a global village. There’s no such thing. We live in places. But because of this global limiting, I think we forgot, and we just became place blind. So that’s the beauty of travel. That’s what it’s supposed to be.”

What’s so important about Fogo Island’s geography?

“Everything starts with geography. I probably know more about you by knowing where you grew up than you think. And Fogo Island is shaped by its geography. We’re just about at the same latitude as Paris. The Labrador Current runs along us, one of the coldest ocean currents. Every year, half of Greenland breaks off and drifts down to us, so we get pack ice. The island itself is four times the size of Manhattan, but only 2,500 people live there. It’s still a fishing community.”

And when Zita says she built the inn, I want everyone to know that it just received three Michelin Keys, so this isn’t just any inn.

“The woman who runs the inn said, “Michelin? What’s a tyre company got to say about us?” It’s a nice thing, but to understand the architecture of the inn, you have to understand the vernacular architecture of the island. We built the inn out of wood, as we build everything, and it’s an act of culture, and I think that’s what travel always needs to be.”

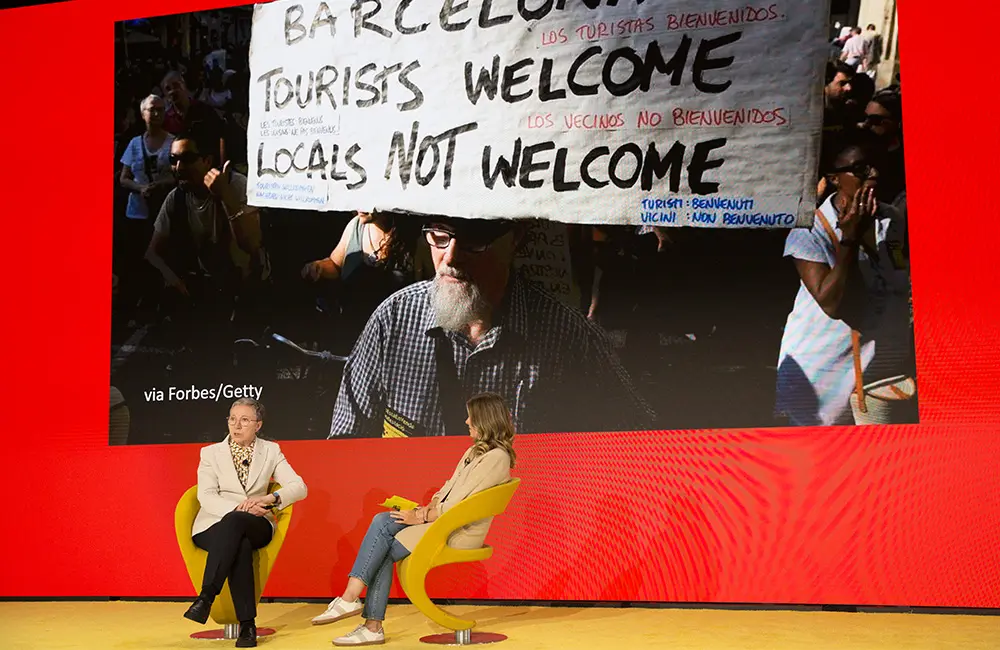

How does community collaboration help push back against overtourism?

“I think we’re a little disoriented as humans at the moment. When we started, there were three keys — not stars — guiding us. None of us had ever done anything in hospitality, so we started community-wide conversations: How do you do this? How is it good for us? How is it good for the visitors? We learned that there are two prerequisites for so-called sustainable tourism.

“The two prerequisites are that it cannot be your only industry. If it is, you’ll end up selling a Frankenstein version of your community, and the scale has to be right for the size of the place, and that’s tricky.

“For example, we were discussing how many rooms there should be, and a woman in the community said, “We are only 2,500 people. We can only love so many people at a time.” So, we decided on 30 rooms. Then we realised 30 is an even number, and we prefer prime numbers. Twenty-nine is an open posture — there’s always room in a 29-room inn. So, we built 29 rooms, which then dictated the business model.

“We decided to create a luxury inn. We could talk for a long time about what luxury is, but it’s largely about connection. Why do people travel? Why should people travel? Travel is supposed to be a social, cultural, and economic phenomenon. I think we’ve lost track of the social and cultural aspects of the promise of travel, which is why things have gone wrong.

“If you think about human societies, they’re built on three pillars: markets, governments, and communities. When they’re out of balance, we don’t have a good world. You wouldn’t want to live in a world that’s all business — you’d get locked up, and it wouldn’t necessarily be good. And you wouldn’t want to live in a world that’s all government.

“I think we’re out of balance in the travel sector; it’s too driven by the market. Governments are starting to realise that infrastructure for welcoming visitors isn’t there in many cases, especially at the local level. Communities are also beginning to figure out their role. They’re realising they need to stop fighting amongst themselves and come together to decide how they want to welcome people. That’s the moment we’re in.”

Did you ever have any pushback from locals about the inn?

“No, not really. I grew up on the island, and so when I came home, one man said, “I don’t think you came home to make things worse.” That was an expression of trust.

“In the beginning, 80% of the people thought, “What is this exactly, and what’s it got to do with me? I don’t really understand what it is.” 10% thought, “This is the worst thing I have ever heard. We don’t want more people coming,” and 10% thought, “Wow, this is amazing.” And so our job was to go slowly and keep engaged with people in the community because they own it.

“Our business model was a bit unusual, and then slowly, as it got built, it actually did happen, and people could start to see themselves in it. We also have a program that invites everyone from the island to come and stay at the end because they own it.

“So, to different models. This is maybe a radical model. If someone is an owner or investor or working in a big corporate chain, I don’t expect you to get up tomorrow morning and put the ownership of the inns in your hotels in the hands of the communities, but I do expect that you can learn from this model, which is radically different.”

Tell us more about Shorefast

“I asked myself, what are the most important things? Well, obviously, nature and culture are the most important things. How do we build economies that support nature and culture? I think the economy now must do that and can do that.”

“Shorefast is about building economies that support nature and culture. Canada has 4,500 incorporated communities, and we’re a country of communities. You have to be able to start from the ground up, think about your economy, and plan top down. I think we’ve been missing, as humans, the ground-up planning. We focus on development from the ground up, not just investment. We’ve built artist studios, have an artist residency program, and more. Shorefast’s mandate is the well-being of the community, not any individual.”

“So our model is that if I die tomorrow, it doesn’t really matter. I don’t own it. There’s nothing that needs to be cleaned off the old; it’s the mandate of shortfalls, which is the well-being of that community.”

What’s next for Fogo Island Inn and Shorefast?

“We need to build a global network of intensely local places. Place holds everything we care about—our culture and our wellbeing. If the economy isn’t serving place, then what is it for? Travel and hospitality are everywhere on the planet, so if we’re not leading this change, no one else will.”

Would you ever consider opening another inn?

“No, but I am helping other communities understand the process. It’s all about how you go about building something that’s great for both visitors and locals.”

For more, head to fogoislandinn.ca and shorefast.org

The Skift Global Forum returned to New York City for its eleventh year and ran from 17 to 19 September 2024. Since its inception, the forum has been instrumental in shaping the future of the travel industry. In 2024, the global theme was Travel’s Great Renewal (and Reckoning), addressing the industry’s path forward amid economic uncertainties, political challenges, climate change, rapid technological shifts, and evolving traveller expectations. Matt Leedham attended as a guest of Skift.

For more details about the event, head to live.skift.com/skift-global-forum